In 1232, King’s physician Ness Ramsay removed a hairball (trichobezoar) from the stomach of Alexander II.

Legend has it that Ness got X-ray vision by drinking a soup made from a white snake which allowed him to complete the procedure without error.

In 1232, King’s physician Ness Ramsay removed a hairball (trichobezoar) from the stomach of Alexander II.

Legend has it that Ness got X-ray vision by drinking a soup made from a white snake which allowed him to complete the procedure without error.

Summer 1970: a rare form of typhoid is infecting people in Edinburgh. Dr Nancy Conn, a bacteriologist at Western General, finds the source and prevents a major outbreak with detective work and sanitary towels.

Dr Nancy Conn is one of Scotland’s unsung women in STEM. I try to tell her story here.

Typhoid was and is uncommon in Scotland. Apart from an outbreak in Aberdeen in the 60s, most cases are linked to overseas travel. The Edinburgh outbreak was different. It was mainly children who were being infected, from different parts of the city.

None of them had ever been abroad and none had any link to India, where this rare strain of the Salmonella typhi bacterium comes from. Dr Conn sat with the patients and interviewed them in detail. Many were senseless with fever. She interviewed their friends and families too.

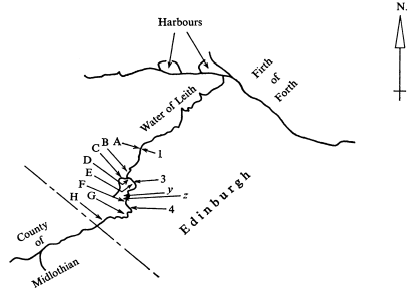

Only one thing seemed to link them– they had all played, fished, or picnicked at the Water of Leith–some had drunk the water. Dr Conn mapped out where the patients had been, but it covered a sizable stretch of a fairly polluted river.

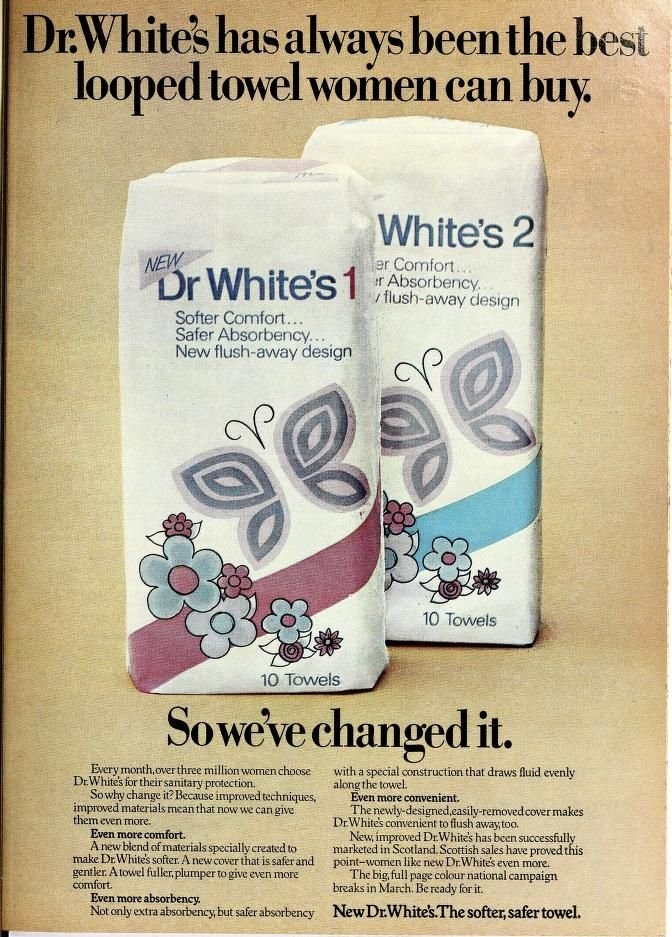

Dr Conn set out to test the river water across the whole area the children had played. The standard protocol for collecting bacteria, known as Moore swabs, kept failing, got muddy and disintegrated in the fast, dirty river. Dr Conn made her own sturdy replacement samplers.

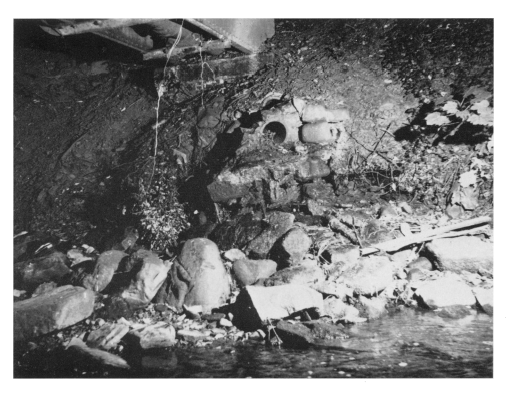

The sanitary towels, after being sunk in the river, were taken back to the lab and cultured. Some had collected the bacterium. Just upstream from the first one that came back positive, Dr Conn found a surface water drain outlet. Problem is, typhoid shouldn’t be in rain water.

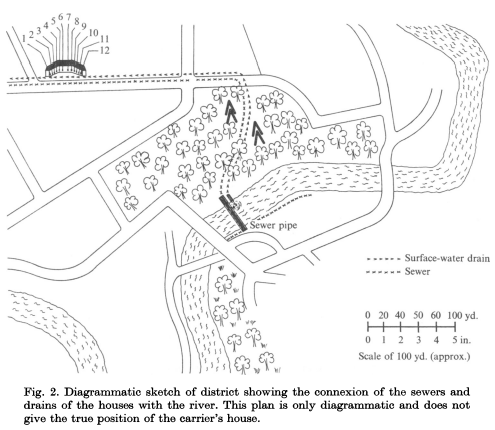

The outlet drained rain and surface water from all of the north of Colinton. Dr Conn called the City Engineers. She gave them packs of Dr White’s No. 1 sanitary towels and showed them how to use them. They put them down every drain and manhole north of the river to sample.

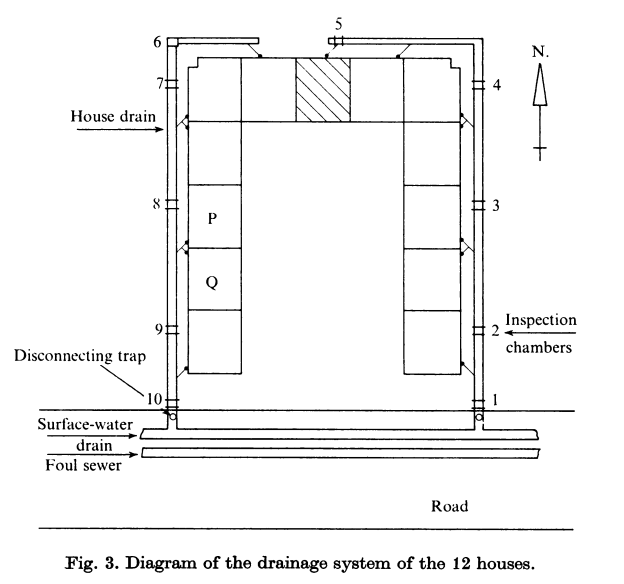

Like before in the river, Dr Conn cultured the samples in the lab and narrowed in on the source: one surface water drain that ran by one particular block of houses. The engineers dug up the road to investigate.The number of typhoid cases was rising.

Sewer pipes are always installed below surface water drains for safety (in case the sewer leaks). When the housing block was built in the 1890s, the position of the pipes was switched, and so got connected up to the wrong outlets by the city.

Dr Conn took samples from the sludge traps of the 12 houses in the block and narrowed the source of the typhoid down to 2 houses (P and Q). To spare the residents embarrassment, she asked all houses to take part in a “survey” and collected samples from everyone.

The source was a 76 year old woman who lived alone. She had never once been ill. She had never been abroad. She had lived in that house for 13 years. If not for Dr Conn and the faulty drains, she’d never have known she was an asymptomatic carrier of a rare Asiatic typhoid.

The carrier was identified 2 weeks before the last admitted typhoid case thanks to Dr Conn working flat out for 2 months. The carrier got treatment and the sewers were fixed, though they both remained positive for several months. So how did she become a healthy carrier?

Dr Conn interviewed her but, in short, nobody knows. She lived alone for most of her life, except with her father, who was a horse vet in the second Boer War and did travel afterwards. Maybe he was also an asymptomatic carrier of Salmonella typhi K1 and she got it from him?

Nancy Conn’s quick and methodical investigation stopped the outbreak of typhoid in Edinburgh. Folk stopped drinking from the Water of Leith and eventually the river got cleaned up. This photo is from the 1983 “Operation Riverbank” in Leith.

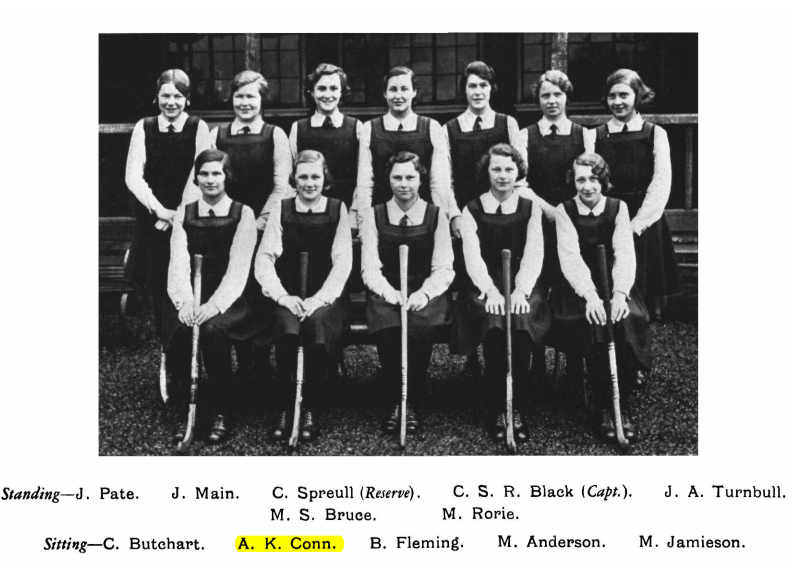

Dr Agnes “Nancy” Kirkland Conn retired in 1979 and died in March 2013 aged 93. A Broughty Ferry lass, she went to Dundee High then did history and later medicine at the University of St Andrews. She also played hockey for Scotland.

POSTSCRIPT: So I said Dr Conn is an unsung hero, but she does appear in Sara Sheridan’s “Where are the Women?”. There is an imagined exhibit at the Glasgow Science detailing her work. Unfortunately, this fictitious installation is the only thing I could find for her.

Dr Conn’s 1972 Journal of Hygiene paper on the outbreak: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3861420

Her obituary in the British Medical Journal: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7263 …and here https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/edinburghnews-scotsman-uk/obituary.aspx?n=agnes-conn&pid=184693199 …

Andy Arthur (Twitter: @cocteautriplets) IDed the unlabeled map as Colinton for me.

The photos:

1980s Leith: https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/heritage/25-photos-showing-leith-it-looked-1980s-regeneration-637369 …

The photos of her as a teenager in the 1930s came from the archives of High School of Dundee. http://www.archive.highschoolofdundee.org.uk/default.aspx

And it was in Sara Sheridan’s 2019 book “Where are the Women?” that I first heard about Dr Conn.

For anyone who is a better Wikipedian than I am, I started a wiki page for Dr Conn https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nancy_Conn Please chip in!

Filed under things you didn’t know could kill you:

In 1900, Alexander Crighton, aged 11, from Montrose, died after a single orange pip got stuck in his intestine. It created a small lesion which became gangrenous. He died within a week.

Always chew your pips!

Dundee Courier, 18th December 1900. pg. 4

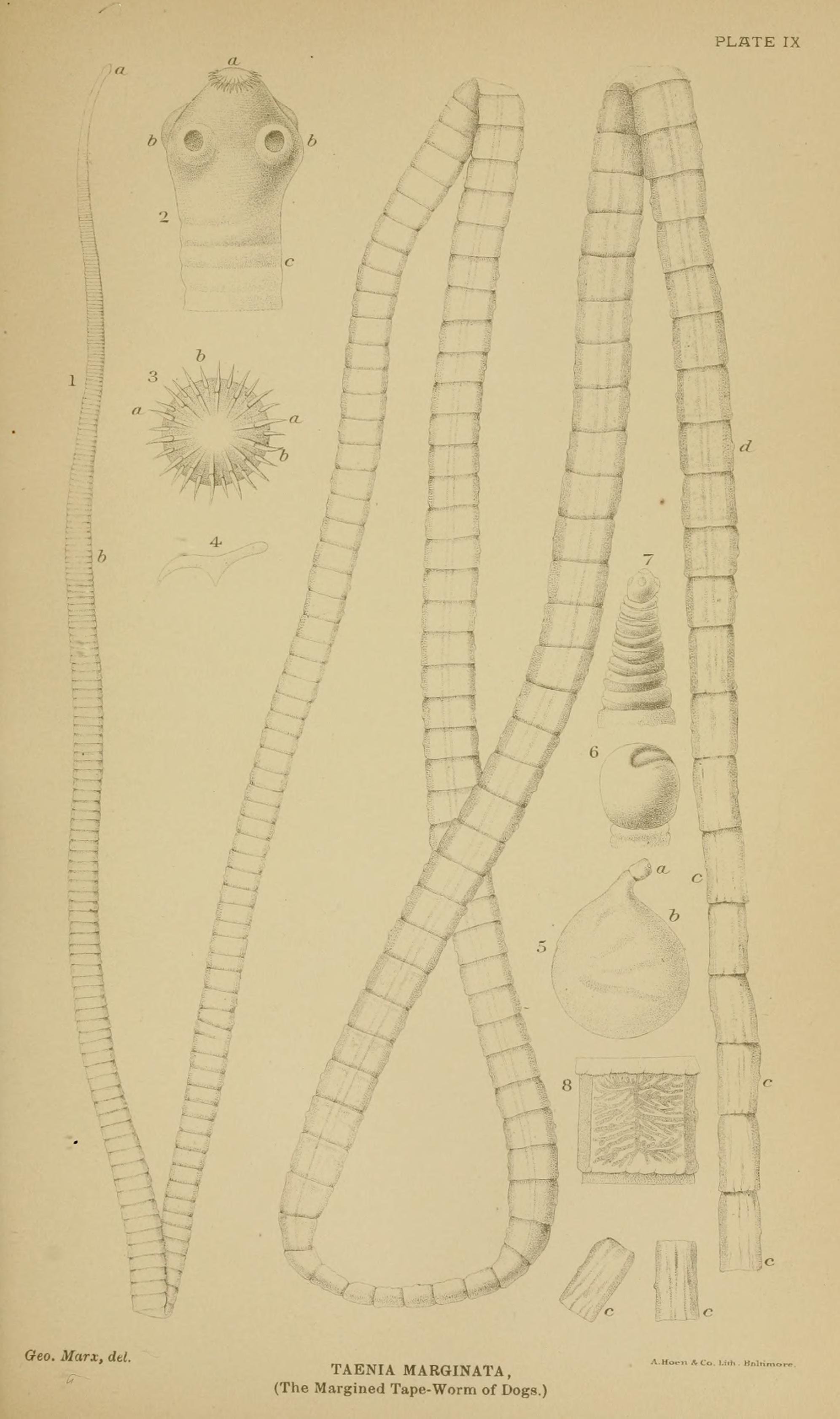

In August 1809, an unusually long tapeworm (Taenia) was removed from a patient in Perth. The world record for a human tapeworm is 82ft (recorded in 1978). The Perth tapeworm measured in at just shy of 150ft… when it snapped.

Perthshire Courier, 31st August 1809, pg. 3

In Fife mining communities a burn on the skin was thought to be cured by holding the afflicted body part close to a flame. The fire was supposed to “draw oot the heat” from the burn.

Simpkins, J.E., MacLagan, R.C., and D. Rorie (1914) County Folklore Vol. VII. – Examples of printed folk-lore concerning Fife with some notes on Clackmannan and Kinross-shires. Sidgewick and Jackson, London. pg. 408

On Good Friday 1882, 147 people in Inverness became severely ill after eating hot cross buns. While not fatal, they all experienced vomiting, tremors, and a dry throat. An unidentified alkaloid poison was found in the spice mix. The case was never solved.

To be honest though, hot cross buns do that at the best of times…

Dundee Courier. 11th April 1882. pg. 4

Inverness Courier. 13th June 1882. pg. 2

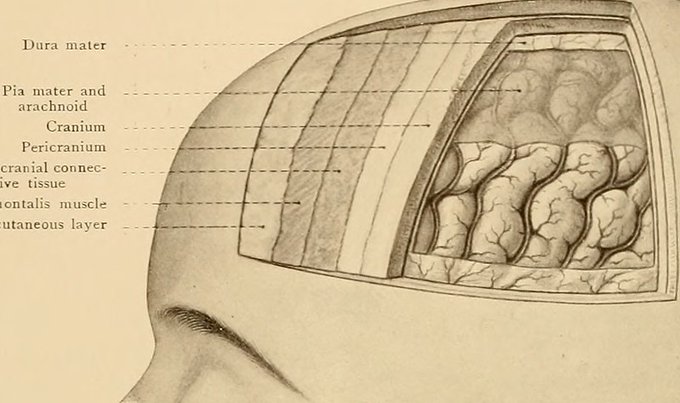

23rd Feb 1715. A “high ryot” started at Pittenweem after William Bell Jr., bailie, called Robert Cook, advocate, “mad and light in the head” and said that his “pericranium was wrang”.

An oddly specific burn if ever there was one.

Cook, D. (ed.) Annals of Pittenweem: being notes and extracts from the ancient records of that burgh, 1526-1793. Lewis Russell, Anstruther. pp.132-133

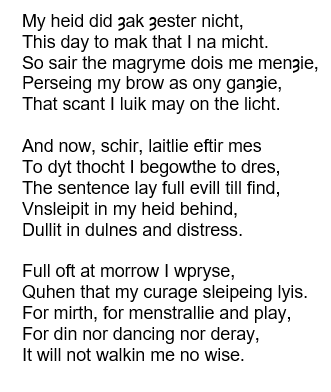

Not many poems about migraines out there. “On his Heidake” was written by Scottish makar William Dunbar about 1500 to 1513 to explain a lack of productivity to his patron and benefactor, James IV.

Rough Translation:

My head did ache last night,

so much that I cannot write poetry today.

So painfully the migraine does disable me,

piercing my brow just like any arrow,

that I can scarcely look at the lightAnd now, Sire, shortly after mass,

though I tried to begin to write,

the sense of it lurked very hard to find,

deep down sleepless in my head,

dulled in dullness and distressVery often in the morning I get up

when my spirit lies sleeping.

Neither for mirth, for minstrelsy and play,

nor for noise nor dancing nor revelry,

it will not awaken in me at all.

Folk in the Northeast believed the following would cure warts.

Rub the wart with snails,

Secretly rub the wart on a cheating husband (he would get your wart),

Lick it every morning,

Rub it with dust from crossroads while saying the words:

“A’m ane, the wart’s twa,

The first ane it comes by

Taks the warts awa.”,

Wash it with water that has collected on a boulder,

Rub with meat, bury said meat, and the wart will “decompose” as the meat does.,

Rub with sack of barley–whoever eats the grains, gets your wart,

Gregor, W. (1881) Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North-East of Scotland. Elliot Stock, London. 238pp.

From 1903 to 1907, Blantyre was known as “Lanarkshire Lourdes” because of the “miracles” of William Rae, a bonesetter. Known as the “Bloodless Surgeon” he saw as many 360 patients a day and once helped 100 children to walk again in 24hrs.

Penny Illustrated News. 2nd July 1904. pg. 4.