Muriel Thompson (1875-1939) was a Scottish racing driver, suffragist, an WW1 ambulance driver. In 1919, she was known as “the best lady driver that ever lived”. She was the undefeated champion of “reverse-start high-speed blindfold racing”.

Muriel Thompson (1875-1939) was a Scottish racing driver, suffragist, an WW1 ambulance driver. In 1919, she was known as “the best lady driver that ever lived”. She was the undefeated champion of “reverse-start high-speed blindfold racing”.

During the 1831 Reform Riots, Edinburgh Anti-Reformers accidentally advertised details of a private meeting. The unpopular Tory MP, Robert Dundas, had to be smuggled past an angry mob outside the meeting hall. He hid inside a cello case on his porter’s back.

If you have a driving licence, think back to when you were first learning to drive. Maybe you had a relative or friend sit beside you, or maybe you had lessons with an instructor. Now imagine, after your first few experiences behind the wheel, embarking on a drive of 900+ miles from one end of Great Britain to the other, in a brand new car, with 4 passengers on board.

In September 1903, this is the challenge that 19 year old Lizzie Murison faced. She was the first woman to drive a motorcar from Land’s End to John o’ Groats and she did it after half a dozen short lessons, the last one on the night before she set off.

Lizzie Burroughs Murison1some sources give her name as Elizabeth, but Lizzie is what is given on her birth registration and her headstone. I also spell her name Murison as that is name on her headstone and how newspaper reports of her exploits spelt it. was born on the 5th January 1884 at Trumland, Rousay in Orkney, to Robert Mitchell Murison and Margaret McDonald. Lizzie’s father was the gamekeeper for the Trumland estate. In 1885, the Murison family moved to Farmley in Kilkenny where Robert became the factor on an estate there.

Lizzie was apparently part of a musical family; she was a noted violinist in Kilkenny and by 1901 was studying at Miss Jane J. Niven’s private school in Gilmore Place in Edinburgh which prepared girls for musical examinations or university entrance. Perhaps unsurprising for the daughter of a gamekeeper, Lizzie was excellent on a horse and a crack shot with a rifle.

In September 1903, the Automobile Club held their 3rd annual “Reliability Trial” at Crystal Palace–a week-long event where car manufacturers pitted their latest models against each other in various challenges to demonstrate their reliability and durability. Events included long distance tours to other towns and laps of dust-covered tracks to see how comfortable the driver would be in various conditions.

The Paisley-based Arrol-Johnston company sent two of their cars to take part in the trials, but their entry to the competition was revoked after they arrived three minutes too late; all entrants had to arrive at the Palace gates by 12 noon–no exceptions!

Denied the chance to demonstrate the durability and craftsmanship of their vehicle, George Johnston of the Arrol-Johnston company was at a loss. Enter Lizzie B. Murison. A family friend of Johnstons, Lizzie, who had travelled down with the cars from Paisley, volunteered to drive the Arrol-Johnston 12 h.p. “dogcart” back to Paisley from London. She knew that having a woman drive their car for such a long distance would be excellent publicity for the car maker, perhaps more than they would have garnered from success in the trials at Crystal Palace.

In September 1903 there were very few women motorists; whenever a woman got behind the wheel it was sure to make the papers. Earlier that year, Britain’s first female racing driver Dorothy Levitt had shocked Edwardian society by winning her class at speed trials in Southport2https://www.beaulieu.co.uk/news/women-in-motorsport-social-history-dorothy-levitt/, so there was a lot of publicity to be gained from Lizzie’s drive. However, a more daring plan was soon hatched and it was decided that Lizzie would drive from Land’s End to John o’ Groats instead–a trip of around 900 miles!

The dogcart was brought to Penzance and on the night of the 20th September, Lizzie had her first and only lesson on how to operate the car she would head to John o’ Groats in.

At 4pm, on Tuesday 21st September, Lizzie, her four passengers (“a lady and three gentlemen”), and all their luggage left from Land’s End amidst cheers and klaxons from fellow motorists who had turned out to support her. We know that she reached Penzance within 45 minutes and was expected to reach Exeter that evening. Unfortunately, that’s about all we know about how her journey progressed. She had expected to arrive at John o’ Groats on the Saturday, but ended up arriving on Monday afternoon–six days after she set off.

She drove, singlehandedly, 900+ miles on roads that were not built for automobiles. She averaged 180 miles each day over 57.5 hours of driving. Her average speed was 15.5mph and on her longest day of driving covered 213 miles.

In an interview she gave to a journalist from the Northern Ensign and Weekly Gazette, she described the roads in Cornwall and the Highlands and being particularly trying driving and for much of the journey the roads were cloaked in rain and heavy mists. Asked if the journey went well, she replied:

“Yes! I had the good fortune to steer quite clear of all accidents to either man or beasts, although several of my party expected, I believe, to end their journey in glory.”

After arriving at John o’ Groats, she and her friends stayed overnight at the Randall’s Station Hotel in Wick, before setting off for Inverness the next morning. She thus completed more than 1000 miles of driving in one week.

Asked about her accomplishment, Lizzie said that she had no desire for fame as a record breaker and was said to have been humble about the achievement (though given her initial idea about publicity for the Arrol-Johnston Company, her nonchalance might be an invention by her interviewer).

So, why isn’t the story of her ground-breaking journey better known? Arrol-Johnston apparently didn’t advertise their dogcart, which remained in production for another few years, on the strength of her achievement. Newspapers up and down the country reported on her success (though she was only ever referred to as “Miss Murison, an Irish lady”). The picture with Lizzie at the wheel of the dogcart at John o’ Groats appears in many books on early British motoring, but no modern researchers have gone further into Lizzie’s own story; all are happy to reprint the photo with “Miss Murison” in the caption.

I think several factors came together to keep Lizzie B. Murison’s 900-mile drive from being better known. Allow me to speculate:

Lizzie was a family friend of George Johnston, who, within a few months3by 1904 he was no longer listed on any company documents, would acrimoniously leave the company he co-founded to start the All-British Car Company. If Lizzie drove as a favour for George, this could explain why her story was kept out of any press for Arrol-Johnston. The dogcart design of Lizzie’s car was already old-fashioned by 1903, and clearly hearkened back to the “horseless carriage” approach towards car manufacture when other companies were making cars with the engine up front.

While there were very few women in motoring (I mean, like very, very few) before 1903, there was a lot going on in September of that year, that may have created an atmosphere that might have made Lizzie’s accomplishment less exciting. The Ladies’ Automobile Club was newly founded and was in the news in September promoting broader participation in motoring events by women. Members of the club were almost all from the upper or landed classes and seemed to really be promoting motoring for ladies in those elevated ranks of society–I am not sure how or if the young single daughter of a gamekeeper would be welcomed in their club.

While Lizzie was driving away from the Reliability Trials at Crystal Palace, Dorothy Levitt was there stealing the show. Levitt was the only female driver at Crystal Palace and almost every report made from the event included something of her story there. From 1903, Dorothy Levitt was the woman in motoring, breaking record after record in speed and distance, and her stories had additional intriguing details like her co-pilot Pomeranian dog and the revolver in her toolkit. Though both Leavitt and Murison challenged Edwardian sensibilities on how single working-class women should behave, Dorothy was a high-speed sprinter to Lizzie’s slow and steady marathoner.

By 1905, the 900-mile journey of “Miss Murison” had all but gone from Britain’s collective memory; Dorothy Leavitt’s journey from Liverpool to London was lauded as record-breaking (“longest drive achieved by a lady driver”). Part of a publicity stunt for De Dion Motors, her 206 mile trip to London is remembered today while the longest drive of Lizzie Murison’s 1903 publicity stunt, 213 miles, has been forgotten.

I wasn’t able to find out much about Lizzie Murison after she returned to Ireland. She married a sea captain, Walter Brennan in 1909 but was widowed the same year. She married Harold Carter Crumplen, an English clerk in 1920. In 1939 she was housekeeper at Worsted Lodge in Cambridgeshire and was still there in 1951. She died aged 70 on 2nd February 1954 and is buried in Burnchurch Graveyard with her parents and siblings in Kilkenny.4http://kilkennygraveyards.blogspot.com/2017/01/burnchurch-graveyard-parish-of.html

Websites

http://kilkennygraveyards.blogspot.com/2017/01/burnchurch-graveyard-parish-of.html

https://rousayremembered.com/lizzie-burroughs-murrison-pioneer-motorist/

https://www.britainbycar.co.uk/isle-of-rousay/552-the-trumland-estate

Newspapers

Gentlewoman – Saturday 19 September 1903

Daily Telegraph & Courier (London) – Wednesday 23 September 1903

Inverness Courier – Friday 02 October 1903

Kilkenny Moderator – Wednesday 07 October 1903

John o’ Groat Journal – Friday 09 October 1903

Print

Dodds, A. (1996) Scotland’s Past in Actions– Making Cars. National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh

Grieves, R. (2002) Wheels around Caithness and Sutherland. Stenlake, Mauchline

Nicholson, T.R. (1970) Passenger Cars, 1863-1904. Macmillan, NY.

Oliver, G.A. (1993) Motor trials and tribulations. HMSO, Edinburgh.

Known as “Incorrigible Nancy”, Agnes Malloy Brown (1848-1915) was one of Scotland’s most-arrested women, racking up over 200 police court appearances in Bo’ness alone. See below for part of her rapsheet…

She was sentenced up to 60 days at a time in Calton Jail for:

drunkenness

breach of peace

throwing tea at her husband

unseemly conduct

biting a woman on the face

bawling in a churchyard

assault with a floor brush…

…smashing police station windows

throwing coal at a crowd

malicious mischief in a police cell

throwing jam-pot at husband

being prostrate in a shop doorway

“disturbing the manse”…

“very filthy language”

being riotous in a tavern

vagrancy

theft of a jacket

breaking fishmongers window

breaking neighbours window

breaking police barracks window…

… threatening minister’s wife

annoying the Town Clerk

climbing inside a distillery kiln

(with daughter) attacking neighbour in her own home

throwing boots at a constable’s house

It’s hard to know Nancy’s true total appearances. She had over 200 in Bo’ness Burgh Court (Police Court) and also appeared in Linlithgow Sheriff and Edinburgh City Burgh Courts. Other contenders for the title at the time included Edinburgh’s Flora Smith, who had her 169th appearance in March 1911, and Dundee’s Ann Dolan Hall (who had an unconfirmed 232 appearances in Edinburgh City Court in March 1902).

When her landlord tried to evict elderly Newburgh (in Fife) woman, Jean Ford (d. 1811), she went to his house and pretended to be a witch. Waiting until she could be seen, she waved her walking stick about and made odd noises. She lived rent free until her death.

In 1940 Ballachulish man, Sandy MacDonald, escaped occupied France with two other Highlanders by speaking Gaelic and posing as Ukrainians. A year before the Soviets joined the war, the “Ukrainians” were free to go.

The other men were William Kemp and James Wilson. Asked in French what country he came from, Kemp replied, “Ardnamurchan”.

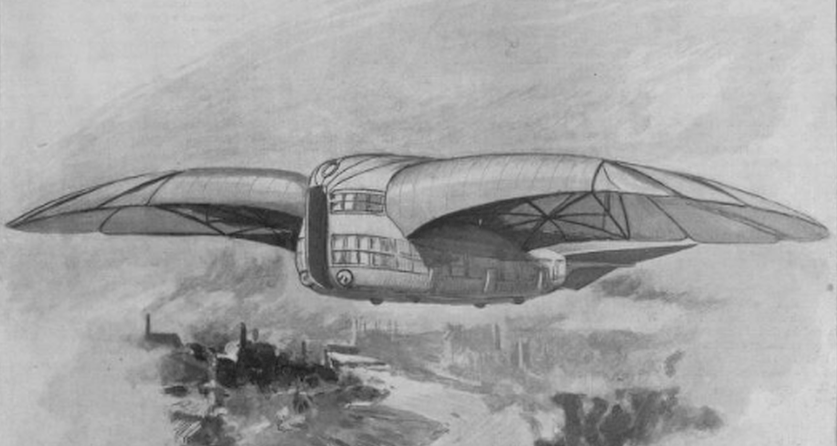

In 1898, Banchory man “Fleein Geordie” Davidson gave the world his “Flying Machine of the Future”.

His “Air-Car Monoplane” would have steam propellers under “wings of a bird”.

He managed a “hop” in an earlier model at Inchmarlo before crashing into a tree.

Below are sketches and diagrams of the air-car taken from an 1898 article entitled “The Modern Icarus – The Newest of Flight Machines” which appeared in the English Illustrated Magazine.

Geordie moved to Colorado in US and continued work on flying machines. Pictured here is his “Gyropter” which was again steam-powered. According to an article in Scientific American, it did manage to lift itself off the ground for a few seconds at a time, before the boiler exploded and destroyed the whole thing.

The Sphere. 25th August 1900. pg. 31

Aberdeen Evening Express. 1st April 1989. pg. 14

Scottish Notes and Queries. Vol. 12, pg. 41

Banffshire Reporter. 17th September 1898, pg. 3

Aberdeen Press and Journal. 7th September 1898. pg. 6

Gunston, P. (1977) Helicopters at War. Chartwell, Secaucus, NJ. p.13

The Sketch. 23rd April 1913. pg 91.

Here are some images of George L. O. Davidson’s other patents and inventions, which are all great and someone should most definitely build models of them.

GB Patent GB190701960A

GB Patent GB189813700A

GB Patent 13207

On a Sunday afternoon in June 1866, a soggy linen-wrapped package washed ashore on the beach at Skateraw, near Dunbar1(now the site of Torness nuclear power station).

The bundle, tied up in a monogrammed white and blue handkerchief, contained 300 love letters, carefully organized by the date they were received. The letters were postmarked 1861, 1862, and 1863 and had been passed between J.G. Smith Maxwell, Esq. (whose initials were on the handkerchief) and Miss Janet G. Dunlop of Clober.

Mr Smith Maxwell’s address was 42 New Bridge Street, London and Miss Dunlop resided at 13 Gloucester Place, Edinburgh.

Curiously, tucked within the stack of letters was the marriage certificate of James Smith of Craighead and Agnes Graham, daughter of a James Graham, merchant in Glasgow dated 21st November 1815!

Smith and Dunlop were married in August 1863 (the year of the last letter in the bundle) at Janet’s address. It seems that James Smith of Craighead and Agnes Graham were J.G. Smith Maxwell’s parents.

The letters were handed to a Mr Thomson of the local coastguard.

Why did (presumably) J.G. Smith Maxwell throw a bundle of love letters from his now wife and his parents’ marriage certificate into the North Sea?

(James Graham) Smith Maxwell died 4 years later, aged 49. Dunlop would outlive him by 42 years.

Fifeshire Journal (21/June/1866) pg. 7

Caledonian Mercury (7/August/1863) pg. 4

Morning Post (17/January/1870) pg. 8

The Scotsman (2/August/1912) pg.12

On the 12th October 1886, the Maud, captained by William Adams pulled into King William Dock in Dundee after a hard 8 months of whaling around the Davis Strait. In addition to the sundry sea mammals they had captured, on board were 30 survivors from the Trinne, a fellow whaler which had been crushed in the ice and a young Inuit man 1(I use Inuit as an adjective and plural noun, Inuk is singular) named Urio Etwango. 2This is how his name was transliterated by reporters. Surnames were not traditionally used by the Inuit so I write his name in full.

Urio Etwango (also transliterated as Ooriaoo Etwanga) was from Aggijjat (formerly Durban Island) in Nunavut, Canada and was to spend the winter of 1886-7 in Dundee with Captain Adams and his family.

Urio Etwango’s arrival in the city was reported on in the papers and it was remarked that he was the third Inuk to have been brought to Dundee.3Dundee has a problematic history of “exhibiting” indigenous peoples that visited the city, which nowadays we would refer to as a “human zoo” (https://www.scotsman.com/regions/dundee-and-tayside/forgotten-inuit-human-zoo-dundees-whaling-past-1487870) Captain Adams gave a series of lectures in and around Dundee over that winter and Urio Etwango was brought along to fundraisers, galas, and speaking events where he was to put on “demonstrations” of his traditional way of life. Venues included New Hall, Kinnaird Hall, and the Dundee West Poorhouse.

At one lecture, Adams explained that Urio Etwango had approached him and requested to be taken to Scotland for the winter when the Maud returned to Dundee. Adams explained that he “agreed, but on the stipulation that [Urio Etwango] was not to taste intoxicating liquors nor smoke, and that he must be biddable and do all he could to improve himself.” The rest of the lecture (and narrative in almost all the newspaper reports about Urio Etwango) was that the lands on the west of the Davis Strait “lacked civilization and Christianity” and that Captain Adams was doing laudable work on “improving” Urio Etwango in the hopes that he would return home as “an example to his neighbours”.

We don’t know what Urio Etwango’s own motivations were in coming to Dundee; the relationship between Urio Etwango and Adams often appears to have been exploitative, but he clearly made good connections with some Dundonians. At one event after performing songs and dances from his home, he asked a box player to play and danced along. After asking where he could get a melodeon to take back to his wife a Mrs Blyth-Martin of Newport got one for him. He enjoyed learning English and teaching Inuktut to anyone who asked.

On a Saturday afternoon on 30th October 1886, Urio Etwango’s kayak appeared out from Dundee’s Tidal Basin and gave “illustrations of canoe paddling and the mode of seal hunting practised by his countrymen” to throngs of Dundonians that packed the esplanade. To demonstrate how seals were hunted at a distance he threw his ivory-tipped spear at boxes that had been thrown into the water. The crowd standing on the esplanade were wowed by his accuracy (apparently he never missed). He then headed upstream so that everyone lining the esplanade could see him and went as far as the Tay Bridge. He came ashore at 4pm at the boatshed.

After his paddle up the Tay, he was pressed to give a repeat performance. The November weather was too bad to paddle the tay again, so the following Saturday, 2,000 people crowded round the skating pond in Claypotts Park in West Ferry to see Urio Etwango throw spears and floating boxes. The Dundee Courier described his kayak: “ [it is] different from that used by Eastlanders [Greenlanders], it being constructed to carry[…] his wife sitting behind and a child in front[…]the Eastlander’s canoe only carries one person.

From all of his public appearances with Captain Adams, Urio Etwango collected about £17, which he used to buy a rifle, a shotgun, and ammunition. He was given various tools that were though would “prove handy to him in Greenland”. A minister gave him a prayer-book. The Maud left Dundee 12th March 1887 for Greenland. On the 16th it arrived in Lerwick and here Urio Etwango again gave a demonstration of “canoe practise”. He was photographed by J.D. Ratter in Lerwick Harbour. The Shetland Museum and Archives has three photographs of Urio Etwango in their collections.

Urio Etwango’s wife loved her new melodeon and played “There’s nae Luck aboot the Hoose” and “The Keel Row” (to the astonishment of the Dundonians). She had learned to play concertina when their family stayed near American settlements on the Cumberland Gulf. She and other women were given “gaudy petticoats”. It was reported that Urio Etwango asked Captain Adams if he could return to Scotland the following year with his wife and child, though he never did.

In September 1889, Captain Adams tried to find Urio Etwango and his tribe but reluctantly had to leave soon after arriving due to bad ice conditions.

I havent found what became of Urio Etwango after he returned home. Captain Adams made his last whaling trip to the area in 1890 but died on the return journey in Caithness.

This was a fun story to research and I thank Julie Cumming for the tip. The newspaper articles about Urio Etwango were rife with the racist and colonialist language that you might expect of the Victorian era. I left out anything I thought unreliable (i.e. heavy colonialism, Christian saviourism etc.) due to the way it was reported. If anyone knows anything about Urio Etwango or his paddle on the Tay, let me know!

Buchan and East Aberdeenshire Observer (15/Mar/1887, pg.2; 16/Sep/1887, pg.3)

Dundee Evening Telegraph (1/Nov/1886, pg. 3; 9/Nov/1886, pg.2)

Dundee Courier (8/Nov/1886, pg.3; 12/Jan/1887, pg.2; 24/Jan/1887 pg.2; 12/Sep/1889, pg.3)

Scott Polar Research Institute. “Adams, William (Snr.) (d.1890)” https://www.freezeframe.ac.uk/resources/adams-william-snr. Accessed 2/Mar/2021

Sarah Dalrymple, Countess of Dumfries (1654-1744) was said to have had suffered from a “distemper” that caused her to fly across the room and around the garden. Was it witchcraft? None could say. Was she definitely 100% flying about? Robert Wodrow was absolutely certain.

That Sarah could fly was apparently common knowledge at the time and after her death. In a pasquil (a satirical poem) lampooning the Stairs family, a poet had this to say about her:

The airie fiend, for Stairs hath land in Air,

verse from “Satyre on the Familie of Stairs”

Possess another daughter for ther share,

Who, without wings, can with her rumple flye.

No middling-foull did ever mount so high;

Can skip o’er mountains, and o’er steiples soare,

A way to petticoats ne’re known before.

Her flight’s not useless, though she nothing catch;

She’s good for letters when they neid despatch.

When doors and windows shutt, cage her at home,

She’le play the shittlecock through all the roume,

This high flown lady never trades a stair,

To mount her wyse Lord’s castles in the air–

Maidment, J. (ed) (1868) A Book of Scotish Pasquils 1568-1715 [sic]. William Paterson, Edinburgh. pg.179

Wodrow, R. (1842) Analecta: or, Materials for a history of remarckable providences; mostly relating to Scotch ministers and Christians. Vol. 2. Maitland Club, Glasgow pg.4

Thank you to @Flitcraft for letting me know about the pasquil.